How Computer Vision Is Teaching Machines to Read the Wild

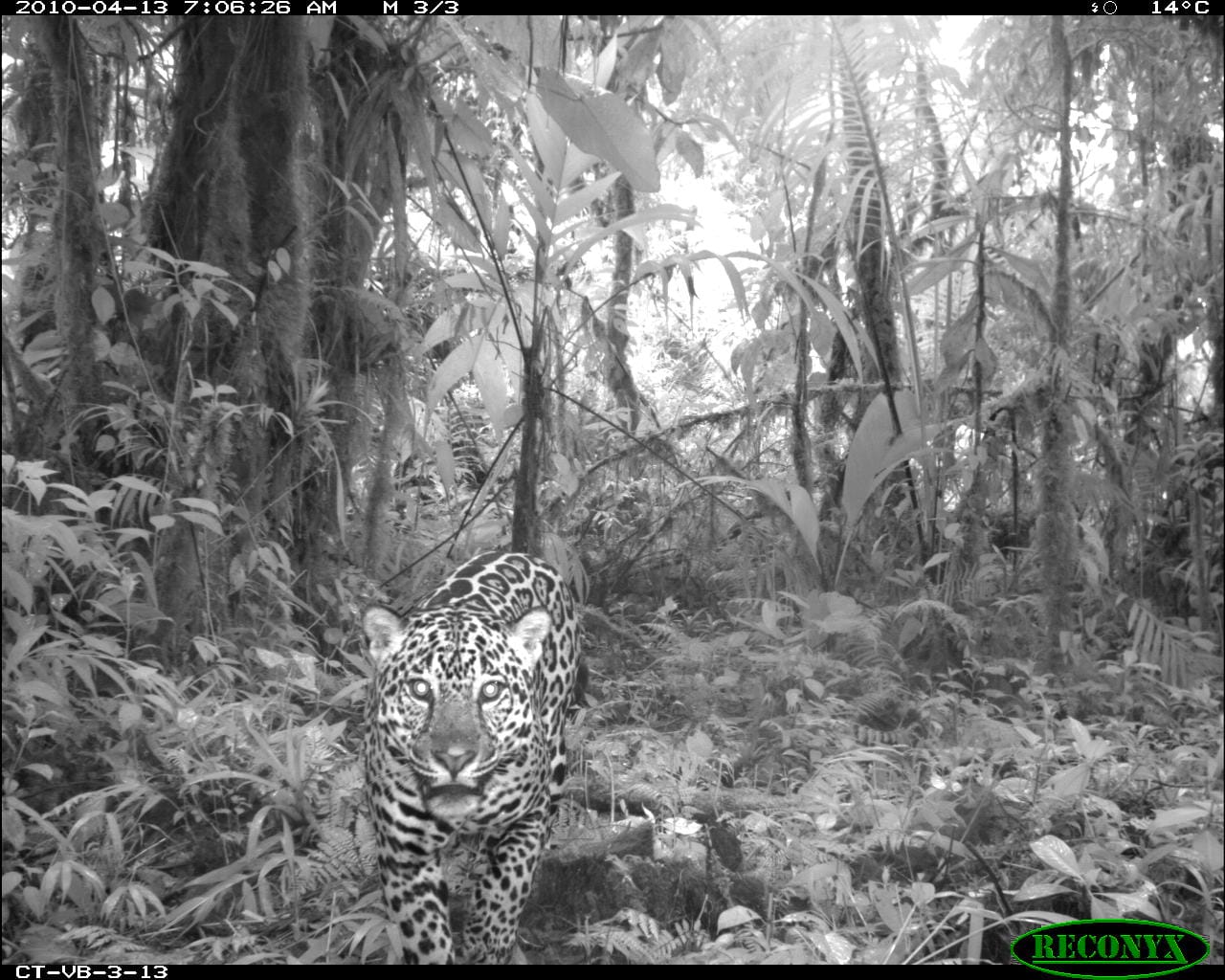

Camera traps offer rare glimpses into the private lives of animals, capturing scenes a human photographer would almost never see: tigers padding through the jungle, strange clashes at watering holes, and species rarely, if ever, caught on camera.

Nature aficionados will be familiar with these photographs, which have appeared in the likes of National Geographic. Social media accounts post captures that are, by turns, amusing, eerie, and beautiful.

But camera trap photographs are not just aesthetic novelties. They are crucial research tools, documenting aspects of natural history otherwise unknowable. They offer perspectives on the habits and abundance of these creatures that can be crucial to their conservation.

The thing is, camera traps snare millions of images. Some of them contain important data. Many do not. Computer vision technology makes this incoherent mass of information useful to scientists.

“Applying computer vision to camera trap data parallels the history of the field of computer vision [in general], moving from very constrained, very well-structured data sets to problems in the real world,” says Sara Beery, an assistant professor at MIT and an innovator in the use of computer vision to analyze camera trap photographs.

Setting the first traps

Camera trap images have only recently risen to public consciousness. However, the history of the technology stretches back to the late 19th century. Photographers such as Eadweard Muybridge and Edward Shiras III set up cameras equipped with tripwires. Shiras published numerous wildlife photos snapped using this technique, notably in a 1906 issue of National Geographic.

While many photographers and scientists experimented with camera traps in the ensuing decades, they were not widely used in research and conservation work.

“When I was a field biologist back in the 1980s, there were no camera traps,” says Jorge Ahumada, executive director of Wildlife Insights, one of the primary organizations utilizing computer vision to analyze camera trap images. “The only way to see animals was to walk around and try to find them.”

It was not until the early 1990s that easily usable models became commercially available.

These rudimentary “trail cams,” which used film, were largely marketed to hunters. They were soon adopted by scientists in tracking animals for more benevolent purposes. Digital options became available in the early 2000s.

Modern camera traps are encased in waterproof boxes and are equipped with infrared motion sensors. When a warm object moves past, the digital camera within is triggered. Increased storage capabilities allow cameras to be left outside for months at a time before the images are retrieved. And sleek, streamlined new models can connect to wireless networks, allowing for remote download.

Computer vision comes into the picture

Sorting through this mass of visual data quickly became a problem for scientists.

Even a single camera trap captures a volume of images that requires painstaking and time-consuming analysis. Photos from multiple traps quickly become unmanageable. Scientists have been working on programs that channel this animal surveillance into streams of data that are actually helpful. Computer vision has been essential to this process.

MegaDetector was among the first AI programs targeted toward identifying animals in camera trap images. It resulted from a partnership between Microsoft’s AI for Earth program and a team of scientists who had zeroed in on the problem. Beery was one of the project’s leaders.

Trialed in 2018 and launched in 2019, it filters out blank images or those that don’t contain animals. Camera traps often fire due to other environmental factors and result in images that are of no use to researchers. MegaDetector uses computer vision to zero in on animals and flags those images for additional analysis. It also identifies humans and vehicles.

This program became an essential component of Wildlife Insights, which resulted from a partnership between Google and a consortium of NGOs.

“Because we were a partnership of larger organizations that had been collecting lots of data over the last 15 years, we had the data,” Ahumada recalls. “That was very interesting for Google. They could just start training a model with that information.”

Wildlife Insights debuted in 2019. It includes a further layer of computer vision review, provided by SpeciesNet, which was built as part of the Wildlife Insights program. Once MegaDetector zeroes in on a likely animal, SpeciesNet gets to work on identifying the species, a key tool for researchers focusing on one animal in particular.

“There was no way that this wasn't going to completely change the way that we study the natural world,” Beery recalls.

Ears and eyes in the dark

Camera trap shots are imperfect. That poses a unique challenge for computer vision.

“It's much easier to localize something than it is to categorize it,” Beery says. The patterns that the algorithms seek when they are attempting to categorize are vague and scattered.

“That was a big challenge. That's why we needed to expose the model to these images,” Ahumada laments.

Said images can be blurry, over- or underexposed, and include creatures that have evolved camouflage sophisticated enough to confuse even the most discerning computer vision model. The animal may just be a silhouette in the undergrowth, a nebulous form with glowing eyes and perked ears.

“I've gotten so good at recognizing blurry streaks from different species — you get check marks from rabbits because they hop,” Beery laughs.

Using accurate portraits of particular species taken using traditional cameras to refine the models simply doesn’t work. They do little to refine the chaos of a camera trap photo set. A perfectly centered image of, say, a cheetah looks nothing like a flash of spotted fur. That is why the volume of images utilized in these models is so crucial.

“The models are able to overcome it if they have enough information. Not only the good ones, but also all the bad ones,” Ahumada notes. SpeciesNet can now identify the species of an animal in a camera trap image with 95% accuracy.

Even the deluge of images provided by the partners of these projects, and individual contributors who submit their own images, has not yet entirely overcome the difficulties presented in developing a computer vision model that flawlessly analyzes camera trap images.

“Camera traps are static cameras. They're incredibly autocorrelated,” Beery says. “The numbers that we were seeing in the distribution setting were only valid for the data set that we were training on.”

Picking out obscure patterns against a stable background was a challenge enough. Scaling it to sets of images captured by different cameras, with highly variable backgrounds, was something else entirely. Computer vision still struggles with this problem.

The problem of the individual

The static nature of camera traps has resulted in another challenge to computer vision: identifying rare species and individual animals.

“The long tail of rare categories is still difficult for any AI model,” Beery says. “Add the static sensor problem. You have a couple of images of a rare species, but they're all from one camera. They all look nearly identical to each other. You really don't have enough variation for the model to recognize that species anywhere new.”

Because a rare species of dik-dik, a small antelope, so closely resembles a more common related species, the model may fail to distinguish them, she explains. Their nostrils are differently spaced, a subtle distinction that computer vision may not register, especially from low-quality images.

So too, machine learning struggles to recognize individual animals. Successful models that identify individuals have typically concentrated on animals such as whales, which have recognizable scarring on their tails, or big cats, which have distinctive coat patterns.

Animals that have a more uniform appearance, no pattern, and no predictable scarring are more challenging for computer vision to distinguish. Even patterned creatures can pose a challenge. Beery recalls her early work on snow leopards. “They have long fur that has a tendency to get wet. The pattern changes,” she says.

Technology meets conservation

The robust results from these models, for all their challenges, have resulted in thousands of additional researchers joining the effort to utilize camera trap images.

Local projects have leveraged the power of these open-source technologies. A community in Colombia used Wildlife Insights to analyze images of jaguars, establishing that there was a viable population in the area. They used this information to advocate for the establishment of a Jaguar Corridor in the region, offering a route between several protected areas. They organized the project in a matter of a month, a process accelerated by computer vision analysis.

These technologies are open-source, allowing researchers to utilize them in myriad ways, contributing their camera trap images to the models in exchange.

The models still struggle to capture everything that researchers need, underscoring the importance of new data provided by users.

“If the model has to guess, it's going to guess the common thing,” Beery says. “That's a really big issue in ecology. The rare thing is often the most interesting in terms of science and conservation.”

The researchers are, however, honing in on truly automated identification. “We're very close to fully automating this, no people needed,” Ahumada predicts. Until then, the models must be fed a steady diet of wildlife paparazzi photos. The volume of images analyzed by these models suggests that it’s feeding time.