How Chef Robotics Is Applying Physical AI to Food Manufacturing

Industrial automation is beginning to look different as we enter the era of physical AI. Systems learn to perceive and respond to the physical world rather than follow rigid, preprogrammed motions. Food production is one of the clearest places to see this shift. Labor shortages are reshaping the supply chain, and manufacturers are searching for tools that can scale in ways traditional equipment never could. San Francisco-based Chef Robotics is one of the companies stepping squarely into this moment. Its founder and CEO, Rajat Bhageria, frames the opportunity in very simple terms. “90% of GDP is in the physical world. Half of GDP goes to labor,” he told me in an interview for Remix Reality. “Food is one of the biggest labor forces in the US. It's a gigantic market, and then there's a big labor shortage as well. It's the number one labor shortage in the US.” His view is that robotics, leveraging today's AI, can reshape how physical work gets done, starting with food.

“I believe in a world where robots are going to be everywhere doing jobs that you and I don’t want to do,” he explained. For him, the goal is not to replace workers but to redirect human time toward better work. Food becomes a natural entry point because it touches everyone and depends on a workforce that is increasingly hard to staff.

How Chef Robotics Found Its Path

Before Chef Robotics, Bhageria built a company called ThirdEye, which used computer vision to help people with visual impairments identify the world around them. After that company exited, he knew he wanted to stay in AI, but he also wanted to push more into the physical world. “If we can combine AI computer vision with robotics, then we can actually address that massive market, which is labor,” he said.

His early ideas covered a lot of ground. One option on the table was a home robot that could cook full meals. To sanity-check it, he asked friends whether they would rather own a kitchen robot or order meals made in a robotic ghost kitchen. “Everyone picked the latter,” he told me. That feedback made it clear to him that people want convenience, not another appliance, and it pushed him toward commercial food operations instead of the home.

So he shifted his focus to restaurants and ghost kitchens, where delivery growth from platforms like DoorDash and Uber Eats suggested strong demand. But the economics were not as compelling as they seemed. "Volumes in a restaurant are actually fairly low," he explained. "600 to 800 bowls or burritos a day sounds like a lot, but it's actually not a ton...[most of the activity is] during lunch and dinner rush, which is like four hours total in aggregate. You have to generate an ROI for your robot in four hours a day, which is pretty hard,” he explained.

There was another challenge. Restaurant workers assemble the entire meal. If a robot could not handle every ingredient, customers did not see value. “All the fast casuals were like, no, you need to do it all,” he recalled. That was a dead end for early-stage robotics, which needs training data to expand capabilities. “Doing all these ingredients is really hard right now,” he said.

The breakthrough came when the company shifted from restaurants to large food manufacturers. The logic became obvious. “Now it is truly the case that Bob is doing the salad, and Joe is doing the sauce.” Specialization means robots can automate one step at a time without needing to solve every ingredient on day one. “Now you’re not running four hours a day, you’re running sixteen hours a day every single day.” That volume is what makes the economics work.

“By shipping robots, you get production training data,” Bhageria told me. That idea became the basis for how the company learns and improves. They began with a small set of ingredients and paid close attention to how the robot handled them in real production. “We see the edge cases, we see how it fails, we see all the weird things we never would have expected in the lab,” he said. Each of those moments helps them expand to adjacent ingredients. “If we’ve done edamame, let’s try to do peas,” he explained. The system improves through this daily exposure to real food and real environments. That steady learning is possible because manufacturing lines operate at the scale needed to support this kind of progress.

Building the Operating System for Food Automation

Automating food work starts with deciding where robotics can help. Bhageria says the answer was clear once they looked at how factories actually run. “Where we find the most labor is usually assembly because assembly scales linearly with output,” he said. Cooking, which many assume is a labor bottleneck, rarely is. “Cooking is actually relatively cheap from a labor perspective,” he explained.

Assembly is different. It requires many hands performing precise, repetitive motions hour after hour.

Chef Robotics built ChefOS to make these tasks flexible. “What LLMs do is they’re predicting the next word. Robots don’t need words. They need actions.” Yet unlike language, food cannot be simulated well. “Simulation doesn’t really work,” he said. “We need training data. And this is one key nuance: in robotics, it's not training data you can download from the Internet.” Food is deformable and difficult to simulate.

A loose taxonomy emerged from this work. “There’s stuff that is leafy greens,” he said. “There’s stuff that mashes. There’s sauces. There’s diced. There’s shredded.”

Source: YouTube / Chef Robotics

Chef Robotics is positioning itself as a foundational layer for the next era of food manufacturing. Early ingredients become footholds for new ones, and each deployment strengthens ChefOS. Over time, that process allows the system to take on a wider range of tasks and supports more flexible forms of automation.

The hardware is also designed to support that progression. “We built the system to be very future-proof,” he said. “Any utensil can work with it, even a future utensil.”

As models and sensors improve, the hardware evolves, but the philosophy stays consistent.

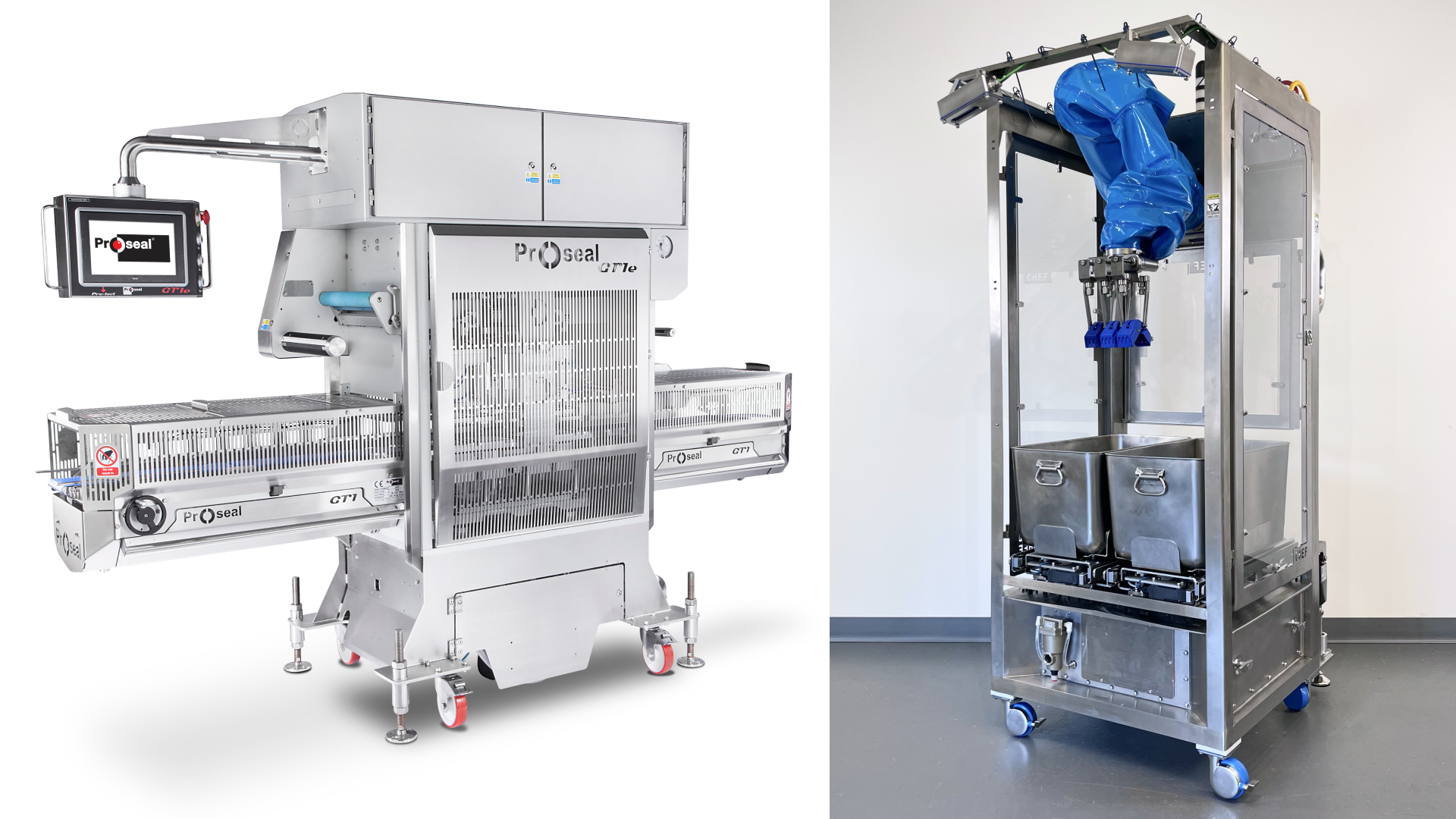

Chef also partners with sealing equipment providers like ILPR and Proseal. “Anytime our customers want to make a meal, you’ve got to seal them,” he explained. “Chef is very much a new technology in the industry. It's not something that our customers are very familiar with. It's also a new business model. So there's a lot of newness, and I think whenever you have a lot of newness, you have to associate it with the old, if you will, to make it less scary.” These companies already supply equipment that food manufacturers depend on, so working with them gives Chef Robotics an easier pat

h into existing lines and immediately gives it a sense of credibility.

Why Robotics as a Service Fits the Future of Food Production

Chef Robotics uses a subscription model. “Our cost structure has recurring costs,” he explained. The robots rely on ongoing compute, updates, monitoring, and improvements to handle the wide variation in real food environments. Unlike traditional equipment, the system continues to learn, which means the software needs to evolve along with each customer’s production line.

The subscription model is a better fit for the kinds of companies adopting the technology. Many mid-market manufacturers prefer avoiding upfront capital expense. “They would much rather pay an annual fee, which is less than the cost of a person,” he said. A subscription allows them to bring automation into their operations without the risk of a large one-time purchase, and it aligns costs directly with the value they expect to get from the system.

The model also reflects the high-mix nature of food production.

Ingredients change, menus shift, and operators introduce new SKUs throughout the year. That requires updates, new policies, and new training data flowing back into ChefOS. A service model gives customers access to those improvements as part of the relationship rather than as a separate purchase. It also ensures the robots continue to perform as ingredients, equipment, and workflows change.

For Chef Robotics, this creates a direct link between deployment and improvement, reinforcing the idea that the robot is not a static machine. It is a system that continues to gain capability on the line, supported by software that evolves alongside it.

Rethinking Robots and Jobs

When people worry about robots taking human jobs, Bhageria sees a misunderstanding. “There’s just a very simple labor shortage,” he told me. The issue is not limited to food production. “It’s not even just in food. In construction, agriculture, and grocery stores, most blue-collar work has labor shortages.” Many of these roles are demanding, offer lower pay, and come with fixed schedules that are hard to sustain. As he put it, “People don't want to do the job at all.”

A major part of the shift is tied to the rise of gig work. Workers have more flexible options than ever. “There’s Uber, and there’s DoorDash, and you’re working on your own hours, and you get paid more, and if you’re tired, you just say, hey, I’m going home for the day.” It is difficult for traditional employers in food production or agriculture to compete with that level of autonomy. “We're not automating anyone,” he said. “It's just there's a shortage."

Bhageria believes concerns about robots replacing workers ignore what past transitions have shown. New technology changes jobs, but it also creates new ones. “These technical revolutions inevitably create more jobs and wealth and prosperity than they take,” he said. Efficiency leads to expansion. “Businesses become more efficient… they become more profitable. And they do more of it.” As companies grow, they open new facilities, develop new product lines, and require new types of work.

To him, robotics fits into that same arc. Automation may shift what certain jobs look like, but it also creates opportunities that did not exist before. The challenge today is not displacement. It is filling roles that industries are already struggling to staff.

It’s a point that comes through clearly on the factory floor. Companies still need to get meals out the door, even as fewer people want these jobs. Tools that can help keep production running are becoming part of how the industry adjusts.